I lead an annual trip to Monteverde National Forest Reserve, near Santa Elena in Costa Rica. The last time I was there, it was in June with a group of IB Environmental Systems students from the Academia Britanica Cuscatleca in El Salvador. As we were settling into our lodgings, a visitor arrived.

Boldly sniffing around the doors to our cabins, was a male Coati or Pizote. With characteristically raised tail, stripey upturned face and strong nimble fingers, the Coati looks like a Rainforest version of a raccoon. Unlike most raccoons, the Coati often shows no fear of human beings, and this one swaggered up to my group of students and casually sniffed us for signs of food. None is totally sure why they stick their tails straight up, perhaps it is to let other Coati’s know where they are. But for a lone Coati such as this, this idea fails to explain it and it seems to me that it is trying to show us who’s the boss.

-Awww…que linda, went up the cry as everyone crowded around to see. I was cautious and warned my class not to get too close. And with good reason. The Costa Rican coati (or white-nosed Coati) Nasua narica has a formidable fighting reputation, with both sharp claws and razor-sharp teeth including canines. They are part of the same group as raccoons in the family Procyonidae, but tend to be more aggressive and fiercer hunters. If they are fed human food, this can cause them to associate humans with lunch and this is a dangerous idea. A coati could easily bite off a human finger. I ask the students to hold their hands up in the air away from the animal, and also to show clearly that they are carrying more food. We take some photos, and allow the animal to pass.

Unfortunately one trio of hapless girls have left their door open, and the male saunters in to inspect the premises. It is safer to open the door and wait for him to come out, which he does eventually after leaving a large dark dropping on the bathroom floor.

Scientists have reported that the Coati are sworn enemies of the highly dominant Cappucin monkeys, having a similar niche in the ecosystem as varied and efficient predators. On an animal survey hike later in the early evening, we witness firm evidence of this theory. A group of 10 coatis ascend into the trees and begin attacking a troop of Cappucin monkeys. An unfortunate mother monkey is separated from her family, and two Coati attack her from both sides. They rip the tiny infant from off of her back where it was clinging in desperation, and in front of my horrified class they murder it in cold blood and take it away in pieces. Our guide tells us that later the Cappucin monkeys may take their revenge.

In the meantime, my students are no longer likely to cry ‘aww…que linda’ next time they see a male Coati inspecting the cabins. However, like some of their human counterparts, they do have a certain roguish charm and I am always delighted to see one – Although when I do; I show them the same respect that I would if I had met Al Capone on a stroll in the rain-forest.

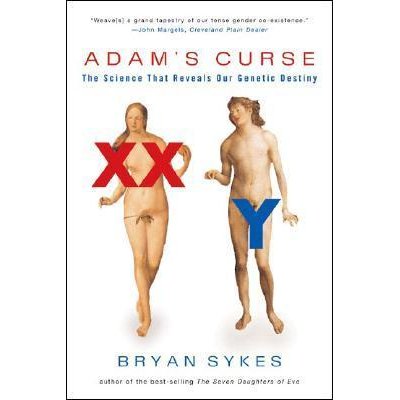

(photo of author with Pizote in Tamatin, Costa Rica)